SPECIAL REPORT Mon, 01/17/2011 9:17 AM |

Anti-Ahmadi pogrom alive and well

The Jakarta Post

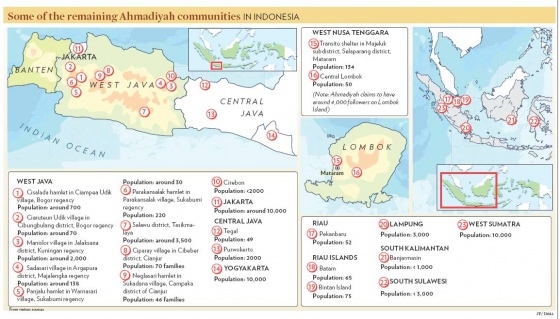

For decades, the violence against the followers of the Ahmadiyah sect has continued without an end in sight. The Jakarta Post’s Arghea Desafti Hapsari explores the root causes of the violence by visiting several Ahamdiyah enclaves in the archipelago. Here are the stories:

Aftermath: Two members of the police mobile brigade guard houses ransacked by a mob in an Ahmadiyah community center in the Ciampea subdistrict of Bogor, West Java, in this photo taken on Oct. 1, 2010. Non-assimilation into the community by some members of the Ahmadiyah Islamic sect has been cited as among the triggers for the attacks by mainstream Islamic mobs. JP/Theresia Sufa

The houses are separated by a dirt road running a few hundreds meters from other houses in Ketapang hamlet in Gegerung village, West Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara.

Every once in a while the owners return from a refugee shelter in the provincial capital Mataram — where they have taken shelter since 2006 — to tend to their farms and guard what is left of their homes.

The ransacked houses are among the countless witnesses to the unfolding tragedy of the endless persecution of the Ahmadiyah faith and its 200,000 followers across the archipelago.

While early incidents of violence against the Ahmadis by mainstream Islamic hardliners — who insist Ahmadiyah is heretical — date back to the early 1950s, it was not until 2005 that the hostility intensified dramatically. In 2010 alone, there were at least 10 recorded attacks against the minority sect.

While the Ahmadis identify themselves as Muslims and follow the Koran, they believe Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who founded the sect in 1889, was a prophet and also the messiah. This goes against the belief of mainstream Muslims who insist Muhammad was the last prophet.

But the root causes of violence may not be limited to differences in theological interpretation, a claim regularly spouted by hardliners.

Allegations that Ahmadis tend not to assimilate into the general population have also played a great role in fuelling mainstream resentment against them.

The locals in a hamlet in Pancor village, East Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, recounted how the Ahmadis set themselves apart from the other villagers.

The hamlet was the scene of several attacks on the Ahmadis in 2002 that forced 83 Ahmadi families to flee their houses and take refuge in Mataram.

“That’s where the houses of the Ahmadis were,” Fitri, a resident of Kampung Baru Baluo, a hamlet in the heart of Pancor, points out to plots run over by wild bushes hiding the stone foundations that were once houses.

The abandoned land is located close to the hamlet perimeter.

“They built a cluster of houses there. When they had new members, they would buy them plots of land nearby to build houses,” Fitri said.

“The locals knew them of course. After all, we were neighbors long before the attacks.”

Another local, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the locals were never really close to the Ahmadis as the latter were viewed as being different.

She said the Ahmadis never visited other residents in the hamlet.

“In turn we never visited them as well,” she said, adding that residents’ interactions with the Ahmadis were limited to the marketplace.

Similar stories were also shared by Gegerung village residents, who forced local Ahmadis out of their homes in Ketapang hamlet in 2006 due to allegations that they did not want to assimilate.

In November last year, Ahmadis planned to return to Ketapang only to be evicted again at the request of Gegerung residents, despite exhortations by Ketapang hamlet leader Muntahar that the Ahmadis did get along with other residents.

He recounted a time when Ahmadis helped other villagers build the village mosque.

“They even contributed money for the construction,” he said. “However, the money was returned once the locals found out about the difference in doctrines.”

Allegations of non-assimilation have also plagued Ahmadis in Parung, Bogor, where the sect built a 15-hectare compound to house followers.

An attack in July 2005 by hardliners was vigorously supported by locals.

While Jakarta has one of the largest Ahmadiyah communities in the country, the movement has faced little violence in the city as most Ahmadis get along well with neighbors.

A recent attack on an Ahmadiyah mosque in Kebayoran Lama, South Jakarta, launched by outsiders was condemned by locals, who said the Ahmadis contributed much to the community.

“It’s obvious that if Ahmadis can get along with others, there is a reduced risk of their facing hostilities,” Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic University sociologist Musni Umar said.

“In some cases, violence against the Ahmadis is triggered by their way of living, which is exclusive.”

Musni urged Ahmadis to be more active in advocating dialogue and openness with their neighbors so more people would understand that theological differences would not be a point of resentment.

Some Ahmadi communities have begun to make the effort to be more open.

Nurrahim, the secretary-general of the Ahmadiyah community in Manislor village in Kuningan, West Java, said Ahmadiyah was an Islamic organization that upheld the virtue of sacrifice.

“We believe the more we give, the more we receive in return,” he added.

All adherents to the faith commit to allotting 1/16 to 1/10 of their monthly income to the organization, in addition to an annual contribution.

The money is held by the Ahmadiyah center in Jakarta, which disburses the money back to the congregations to finance activities such as charities and other social programs.

Nurrahim said the money was never disbursed to Ahmadiyah members personally. The Ahmadis also refute allegations that they refuse to assimilate.

“We live alongside and with people of other faiths,” said Nur Hidayati, an Ahmadi from Pancor, who was forced to flee her home after the 2002 attacks.

Ahmadiyah spokesman Zafrullah Pontoh said Ahmadis never prohibited others from praying in their mosques and vice versa.

“Our mosque on Jl. Balikpapan [in Central Jakarta] is open to anyone. People in the neighborhood can perform Friday prayer there. So reasoning that we are being attacked because we refuse to assimilate is just unfounded.”

In some cases, attacks on Ahmadiyah have been incited by hardliners living outside the community.

Ahmadis in Cisalada hamlet in Ciampea Udik village in Bogor, West Java, had no problems with locals until the 2005 attacks in Parung — 10 miles from the village — changed everything.

A resident from a neighboring hamlet, Gaos Hanafi, recalled how in the 1970s people from his hamlet would come to Cisalada, where all 700 residents were Ahmadis, to play soccer.

“We were very close back then. I even had relatives there. The Ahmadis and other villagers used to have an open debate about Islam but there was never any violence.”

But the Parung incident stirred resentment that peaked in 2007 when hundreds of people gathered to stage a protest against the renovation of an Ahmadiyah mosque in Cisalada.

Another protest against the mosque and other properties owned by Ahmadis in the hamlet took place in July 2010. Three months later, violence erupted as assailants set fire to five houses, a car and two motorcycles owned by Ahmadis.

Critics rightly alleged that provocation by policymakers and mainstream clerics fuelled the hostility.

Last year Religious Affairs Minister Suryadharma Ali insisted that Ahmadiyah was a heretical sect and “must be disbanded immediately” as its doctrine violated tenets of Islam — a pronouncement that intensified the pogrom against the sect.

Suryadharma claimed he was only reinforcing a fatwa first issued in 1980 by the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) and another in 2005.

In 2008, a joint ministerial decree was issued to ban Ahmadiyah from propagating its teachings.

The fatwa and the decree cited theological differences between Ahmadiyah and mainstream Islam in outlawing the sect.

“The violence has been going on for decades and is likely to continue this year. Hostility is just not the answer,” Musni said.

“It’s time for policymakers and clerics to initiate dialogue with the Ahmadis instead of perpetuating the pogrom through hate speech, unconstitutional decrees and vile sermons.”

— Additional reporting by Panca Nugraha